A Story of Compassion: Nigel Westlake on Ngapa William Cooper

05 April, 2024

Composer Nigel Westlake explains the story behind Ngapa William Cooper, a new collaboration with singer-songwriter Lior and Dr Lou Bennett, ahead of the work’s Sydney Symphony premiere in May.

By Hugh Robertson

In 2014, composer Nigel Westlake and singer/songwriter Lior collaborated together to create a work called Compassion. Taking ancient Arabic and Hebrew texts, with new music written by Westlake, the piece presents a number of different perspectives on hope, tenderness, consideration, kindness and, yes, compassion.

Almost uniquely for a piece of 21st century classical music, it has been a huge hit. Commissioned and premiered by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra it has remained a cornerstone of contemporary Australian music: a recording of the premiere won the ARIA Award for Best Classical Album, excerpts of it are frequently broadcast on radio, and it is regularly performed all around the country – so much so that Westlake has been asked to rework the piece for string quartet and for chamber orchestra, so that more ensembles can perform the piece.

So when Westlake and Lior felt the time was right to work together again, how could they follow that up?

‘For quite a number of years we were searching for the right narrative,’ says Westlake, sitting in his home studio in Sydney. ‘Compassion is a philosophical work, there's no specific narrative, so we thought, ‘let's find an act of compassion that could be a companion work.’

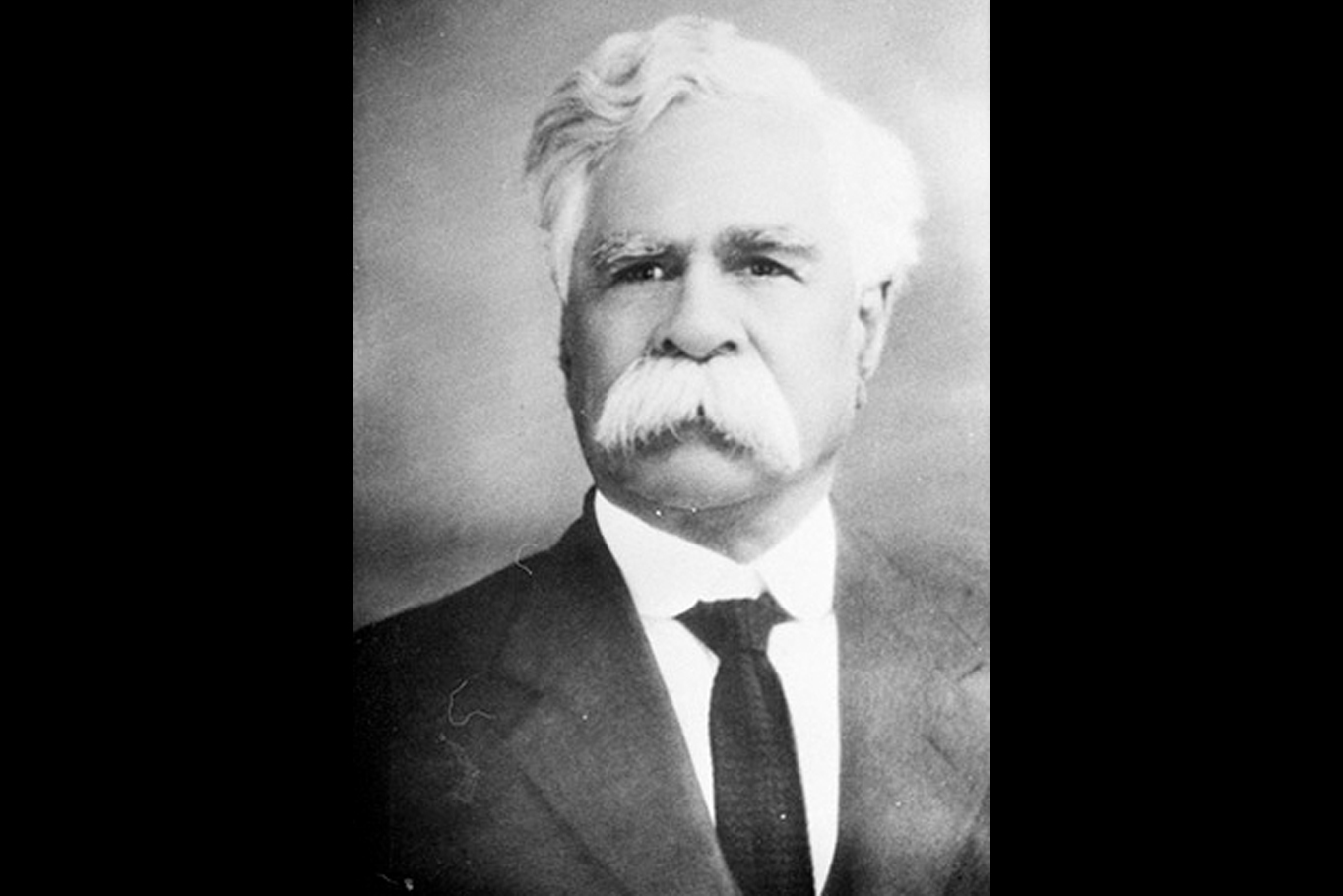

The act of compassion that they found revolves around First Nations activist William Cooper.

Born in 1860, Yorta Yorta man William Cooper is a significant figure in the history of human rights for First Nations people. He was one of the founders of the Australian Aborigines League in 1933, which campaigned for better treatment for Indigenous Australians. Cooper was one of the organisers of a petition to King George V, demanding Indigenous representation in Federal Parliament – a precursor to the Voice to Parliament, nearly a century before that campaign.

In January 1938, Cooper was one of the organisers of a National Day of Mourning to mark the 150th anniversary of the landing of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove, an event that has now become NAIDOC Week, which celebrates and recognises the history, culture and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia.

But Cooper’s compassion and advocacy did not just apply to his own people. In 1938 Cooper was reading the newspaper, searching for any coverage commemorating his son, who had died in the First World War twenty years earlier. Instead what he found was reports of Kristallnacht, when Jewish people had been targeted in widespread rioting and looting across Nazi Germany.

‘He was outraged by what he read,’ says Westlake, picking up the story. ‘He convened a meeting of the Australian Aborigines League, and they voted to create a petition, and hand-deliver that petition to the Nazi consulate in Melbourne. And so they marched from his house in Footscray, in the heat of the Melbourne summer, dressed in their Sunday best, to deliver this petition. And despite the fact that they had made an appointment to see the consulate and hand deliver the documents, the doors, the gates were locked when they arrived.’

‘The fact that this man – who had been denied his rights, the rights of his people, the right to speak language, the rights to participate in any cultural, practice whatsoever, the right to remain on their traditional lands – had the empathy to relate to a culture on the other side of the world, people he'd never met, and be outraged by their predicament, struck us as an extraordinary act of compassion within itself.’

Westlake and Lior had found their subject. Newly-inspired, Lior quickly settled on a framework, working with Melbourne writer Sarah Gory to divide the story into seven sections.

‘Lior would record a vocal part based on these beautiful lyrics he created, just as a completely solo vocal lines,’ says Westlake, describing their writing process. ‘And as was the case when we wrote Compassion, I could almost immediately hear an accompaniment for that.’

Once Lior and Westlake got started, it became clear that they couldn’t properly tell this story without a First Nations perspective in the composition process. They reached out to Dr Lou Bennett, a Yorta Yorta Dja Dja Wurrung singer and composer, who it turns out was actually the perfect person to ask.

‘Lou was very enthusiastic about the idea, and she sort of casually mentioned, “Oh, by the way, I'm a full blood relative of William Cooper,” says Westlake with a laugh. ‘Not only that, she's a really beautiful singer. And she specialises in the ‘rematriation’, as she calls it, of the Yorta Yorta language.

‘So Lior and I sent her some of our early ideas to translate [into Yorta Yorta language], thinking maybe she could sing them. And the recordings she sent back, which she recorded on her phone, were absolutely spine chilling. And we realised we had to involve her in the performance of the work. And so she became an integral piece of the puzzle.

‘She, in the greater sense of the work as it exists now, represents the spirit of William Cooper and the Yorta Yorta culture. And Lior is the storyteller. Most of what Lou sings is in language, and Lior sings in English.’

In addition to his more traditional classical works, Westlake is perhaps best known for his film scores including Babe, Paper Planes, Blueback and Ali’s Wedding, among many others. So perhaps it’s not surprising that he began to think of his part in this project as composing a soundtrack to the life of William Cooper.

‘For me, it was very much like approaching a film score,’ says Westlake. ‘The melodic contour of these beautiful vocal lines, created by Lou and Lior, leave a lot of room for emotive expression, and kind of a sophisticated drama sense that you might find in a movie score.

‘My role was to add the colour and drama of what was happening – what we think he might have been imagining in his mind or whatever the emotional responses to what he was encountering, the anger, the frustration, the sadness. And also elements of optimism: the fact that he spent his life fighting for the rights of his people, even though he seemed to rarely get heard by government or any officials whatsoever. Yet he was determined to continue that fight. And that in itself is very inspirational.

‘So I very much felt that, it was, you know, the sort of music that I would write for a movie about William Cooper.’

Much like Compassion before it, Ngapa William Cooper has started to take on a life of its own. Westlake certainly sees some similarities in the ways in which audiences have been responding to the piece – and he experiences them himself.

‘One of the last sections of the work, I said to Lou that I felt it needed a final moment with her – perhaps some sort of chant or mention of William's life,’ recalls Westlake. ‘That's all I said to her. And she came back with this incredibly powerful song in language. She’s saying goodbye to the spirit of William, she's bidding William farewell and giving him permission to go with the old ones.

‘It just gets me every time.’

‘I don't think you can help but be moved by that.’

‘And there are a number of moments in the work where this sort of thing occurs.’

Premiered just last year, the work has already been performed around the country, at festivals and in major concert halls, with Westlake already having been asked to produce versions for full orchestra and for a chamber ensemble of string quartet with double bass, piano and percussion, and of course the voices of Lior and Bennett.

These Sydney Symphony Orchestra performances in May will present the premiere of a third version of the work, newly arranged for string orchestra.

‘I've taken the smaller chamber version of the work and expanded that into a string orchestra,’ Westlake explains. ‘So we have 18 or 20 strings, percussion, played by [Principal Percussion] Rebecca Lagos, and Andrea Lam playing the piano. It's going to be exciting to hear it brought to life in this new format.’

The other exciting aspect of these Sydney Symphony performances is that Westlake himself will be conducting, continuing a long relationship with the Orchestra that stretches back even before Nigel was born.

Both of Nigel’s parents performed with the Sydney Symphony for many years. His mother, Heather Sumner, was invited to join the Orchestra by our first Chief Conductor Eugene Goossens, in the late 1940s, remaining with them on and off for many decades. It was while a member of the Orchestra that Sumner met Donald Westlake, who came over from Perth in the mid-1950s and had been appointed Principal Clarinet, a post he held (after further studies in Europe) from 1960 until 1978.

Nigel has strong memories of coming to see both of his parents perform in the Orchestra, first at Sydney Town Hall and then the Sydney Opera House once it opened. And his own playing career meant that Nigel got to perform in the Orchestra with his parents in 1978. ‘One of the first recordings I did was The Rite of Spring under Willem van Otterloo,’ recalls Westlake with a smile. ‘My mom was playing violin, my dad was Principal Clarinet, and I was playing second bass clarinet beside Peter Kyng, the Principal Bass Clarinet at that time.’

These upcoming performances of Ngapa William Cooper will be just the next chapter of many in the long association between the Westlake/Sumner family and the Sydney Symphony, and Nigel is convinced you can hear that connection in performance.

‘Whenever I come to the Sydney Symphony, it's always like coming home,’ says Nigel with a smile. ‘Not only did my parents have such a long history, but there are still a number of members that I went to school with at the Conservatorium High School. Many dear friends are part of the Orchestra and it's always an incredibly enriching and wonderful experience to come on board and work with the players.

‘Especially as a conductor conducting my own work,’ he continues. ‘I feel really at home with all the players when I conduct. We're speaking the same language and addressing the same issues. And I'm calling upon them to contribute their ideas and be part of the process.

‘I absolutely love conducting my own work. It’s really lovely to be a part of that.’

SEE NIGEL WESTLAKE WITH THE SYDNEY SYMPHONY