Steven Isserlis on William Walton

31 May, 2023

The acclaimed English cellist discusses William Walton’s Cello Concerto – which he counts among the greatest ever written – ahead of his performances with the Sydney Symphony and Chief Conductor Simone Young in June.

Written by Hugh Robertson

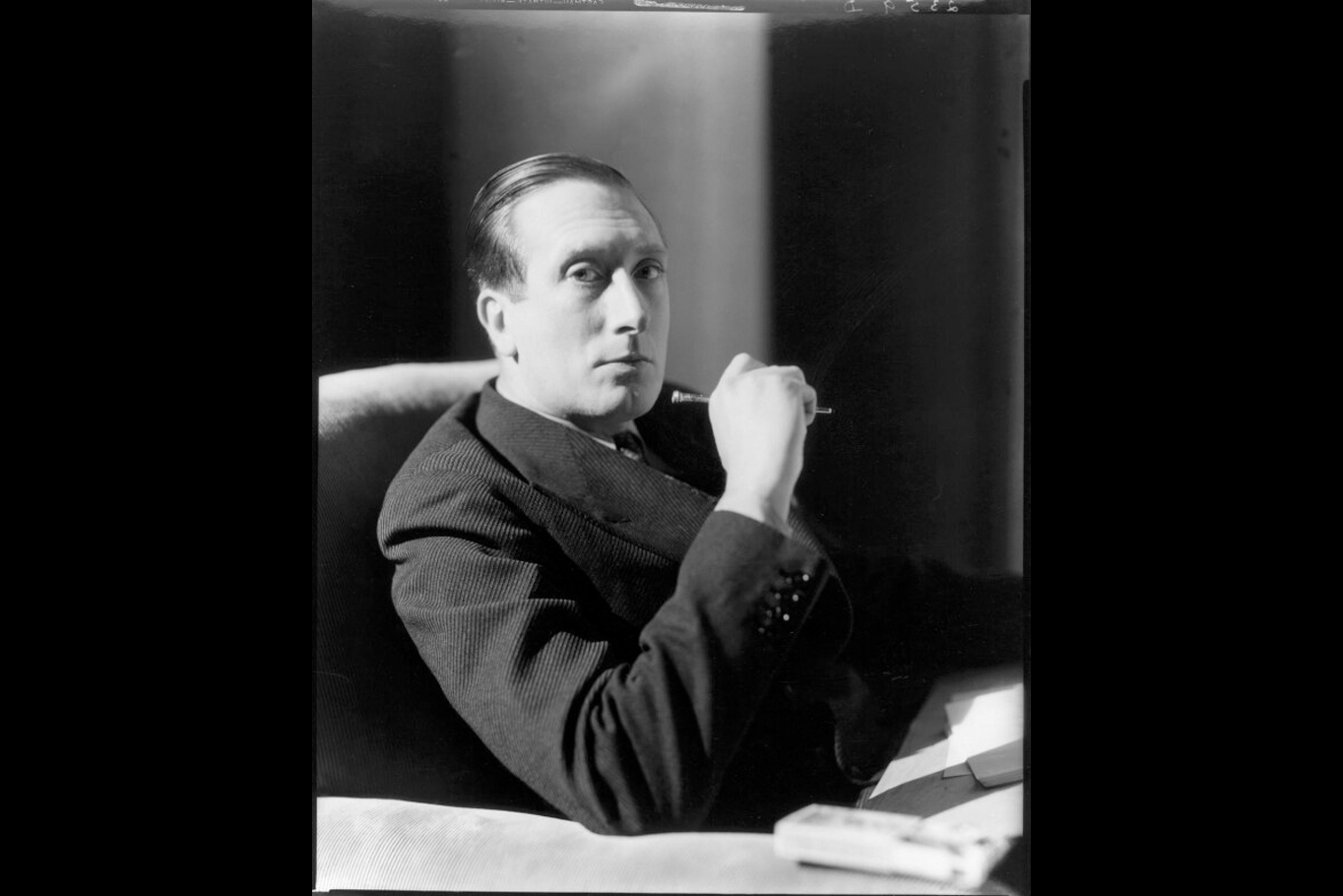

Sir William Walton is a fascinating figure in the history of English music.

He was undoubtedly one of the most significant British composers of the 20th century, ranking alongside Elgar, Vaughan Williams and Britten in terms of impact and influence. He won a scholarship to Christ Church Cathedral School in Oxford, one of the crucibles of English church music; he was acknowledged as one of Britain’s leading composers for most of his life, commissioned to write music for two coronations; he was knighted in 1951 aged just 49.

Despite this British-to-his-bootstraps pedigree, Walton’s music exists somewhat outside the central English canon. When we think of English music of the 20th century it tends to be Vaughan Williams’ larks ascending, or Elgar’s pomp and circumstance, or the bleak coastline of Britten’s Peter Grimes; Walton is always just off to the side.

Part of the reason might be that Walton lived the second half of his life in Italy, on the idyllic island of Ischia, where all that English tradition was washed away by sunshine and sea spray. But musically, too, Walton was always hard to pin down to a certain style or school of composition. He always seemed torn between two impulses: one the one hand, a deep love of Edward Elgar and late 19th-century romanticism, but on the other a desire to move music forward, influenced by jazz and experimenting with rhythm.

His earliest success was the scandalously modern Façade, which was panned by the press when it premiered in 1923 – one publication ran with the headline ‘Drivel they paid to hear’! As the years went on Walton remained inscrutable, ignoring prevailing trends and remaining very much his own man – so much so that his output post-World War II was often dismissed as nostalgic and old-fashioned by a British public hungry for the new and eager to leave the past behind.

But that is a rather unfair characterisation of a hugely inventive and interesting composer. Writing in the music Bible Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Byron Adams said of Walton that his music “has often been too neatly dismissed by a few descriptive tags: ‘bittersweet’, ‘nostalgic’ and, after World War II, ‘same as before’,” which Adams argues ignores the variety and creativity of Walton’s output.

Adams goes on to argue that Walton discovered his compositional voice early in his career and never abandoned it, and that his trademark rhythmic variation and flair for orchestration gives his music "an imperishable glamour".

English cellist Steven Isserlis agrees with that assessment.

“Walton was a truly great composer, I feel, who alas was labelled as ‘unfashionable’ as he grew older,” says Isserlis. “It is entirely to his credit that he refused steadfastly to follow any trends, and continued to produce music in his own, unique voice.”

Isserlis has been at the forefront of the Walton renaissance, and in June he joins the Sydney Symphony and Chief Conductor Simone Young to perform Walton’s Cello Concerto paired with Robert Schumann’s Fourth Symphony.

He recorded the concerto in 2016, a recording that won a slew of awards and received widespread acclaim. “No praise can be too high for Isserlis’s splendid playing, eloquent without being indulgent and technically always in complete command,” wrote MusicWeb International. “Walton's concerto is a delight,” said the New Zealand Herald. “Few cellists could match the sense of playful engagement between soloist and the orchestra around him.”

“I love it,” says Isserlis of the Cello Concerto. “I’ve often said that for me, the four absolute greatest cello concertos – although there are many other great ones as well – are those by Schumann, Dvořák, Elgar and Walton.”

Walton wrote his Cello Concerto in 1957, when he was firmly established at the very peak of British music. He had been knighted in 1951, in recognition of his long and celebrated career that, by that point, had involved writing music for the coronations of two separate English monarchs – his Crown Imperial march was heard at George VI’s and his setting of the Te Deum was commissioned for Elizabeth II. (Demonstrating his continued impact on British music, both pieces were performed at the coronation of Charles III earlier this year.)

The premiere of the Cello Concerto was met with positive if somewhat dismissive reviews. A reviewer of the world premiere in Boston thought that the piece was beautifully written but old-fashioned, describing it as "fine, warm and melodious" but also saying that "what dissonance there is would not alarm an elderly aunt". English critics said similar things, with one remarking that there was little in the work that would have startled an audience in the year that the Titanic met its iceberg (1912).

This criticism wasn’t new for Walton, and in fact he had heard something very similar 20 years earlier upon the premiere of his Violin Concerto, written in 1939 for the great violinist Jascha Heifetz. Many critics wrote that it was overly traditional and too backwards-looking, leading Walton to say in an interview shortly afterwards, “These days it is very sad for a composer to grow old ... I seriously advise all sensitive composers to die at the age of 37. I’ve gone through the first halcyon period and am just about ripe for my critical damnation.”

But Isserlis won’t hear a word against the piece.

“Walton’s concerto is poetic, dramatic, intensely lyrical, and unlike any other concerto – even his own ones for violin and viola,” he says.

“It is a deeply romantic work, very accessible but also profound, and quite original.”

It is also a deeply personal work, evoking not only the people in Walton’s life but also the Italian island of Ischia, where he lived from the mid-1950s until his death in 1983.

“It is said that it was a portrait in sound of his relationship with his fiery wife Susanna – I can believe it,” says Isserlis with a smile. “And the opening really does bring to my mind the sound of the sea lapping on the shore of Ischia. Perhaps there is also some sense of the exotic beauty of the island – not least the garden that Susanna created there.”

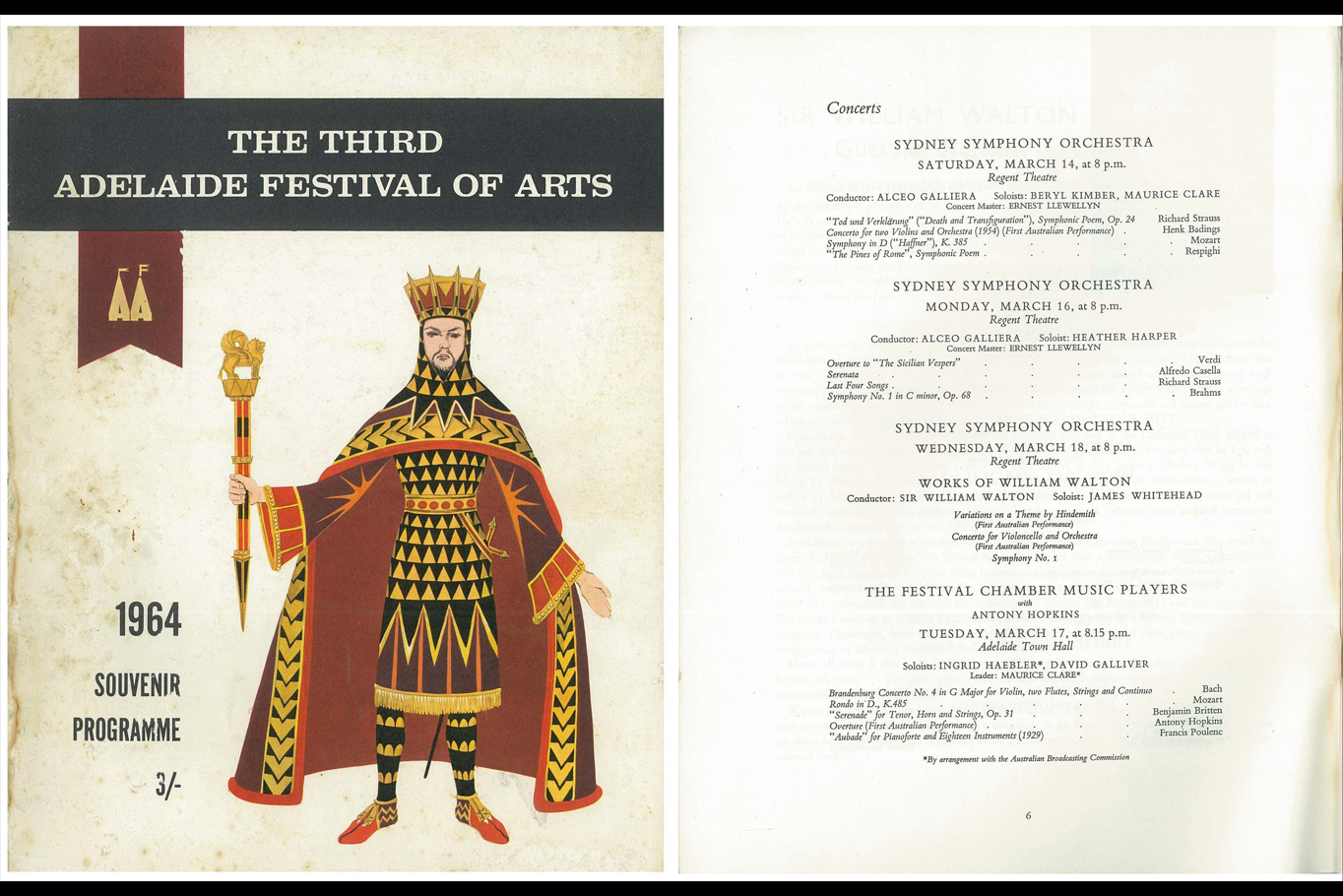

It’s not just Steven Isserlis who has a long and close relationship with this concerto; the Orchestra does too. The Sydney Symphony gave the Australian premiere of the concerto at the Adelaide Festival in 1964, with James Whitehead as soloist and William Walton himself conducting.

Since then the Orchestra has performed the work several times over the years with a number of celebrated cellists, including Paul Tortelier (conducted by Werner Andreas Albert in 1984), Rafael Wallfisch (with Bryden Thomson, 1990) and Peter Wispelwey (with Jeffrey Tate, 2007), the latter performance subsequently released on CD and given five stars by BBC Music Magazine. “This performance... is alive at every point,” wrote their reviewer, “And has an excellent orchestral contribution (the playing of the principal oboist [Diana Doherty] is a lustrous phenomenon).” But 2023 is the first time in more than 15 years that this work will be heard in Sydney.

And how has the passing of the years treated Walton’s concerto? Perhaps we should leave the last word to that same BBC Music Magazine reviewer:

“Walton's Cello Concerto is like a bottle of vintage wine from the composer's home on the Italian island of Ischia… its warmth, finesse and wry serenity are qualities that appeal all the more as time passes.”

Sounds like just the thing for winter in Sydney!