Joyce Yang on Grieg’s Piano Concerto: ‘It Lives on its Own Planet’

07 May, 2024

Grammy-nominated pianist Joyce Yang explores Grieg’s Piano Concerto, a unique work she says ‘doesn't sound like anything else,’ ahead of her performances with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra in May.

By Hugh Robertson

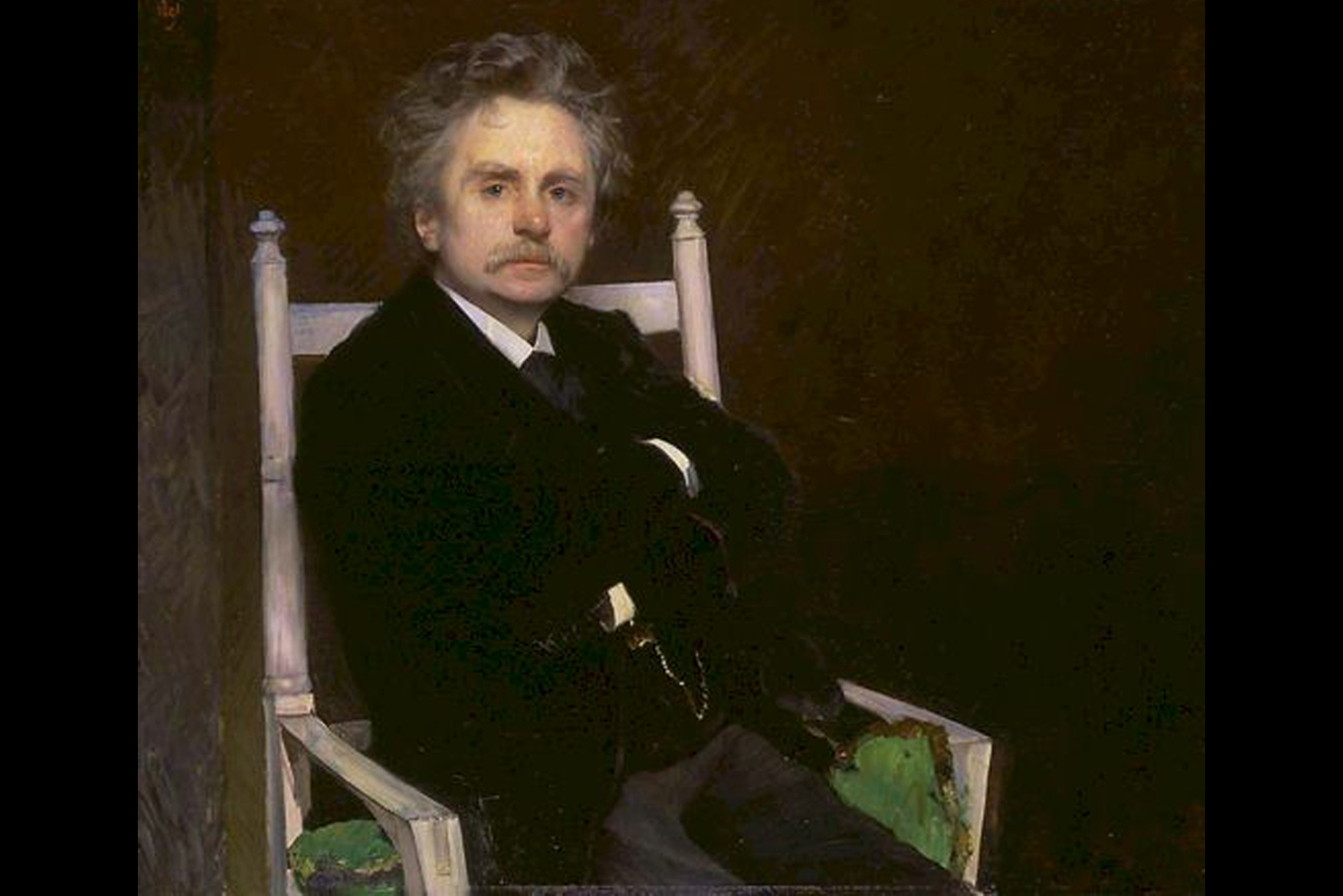

The piano concerto repertoire is rich and varied, with something to suit every taste, from grand heroic themes to delicate, sparkling miniatures; from lush and evocative landscapes to thrilling, edge of your seat virtuosity. But perhaps no piano concerto contains more of those moods all at once – and yet sits apart from them all – than the one written by Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg.

Composed in 1868 Grieg was undoubtedly influenced by Beethoven and the German Romantic style more broadly, yet he weaves Norwegian folk music in to create a piece that is both unique and universal. The critic Bill Parker once wrote, ‘what people hear are the fresh melodies and the enchantment of their poetry,’ describing it as ‘the very prototype of the Romantic Piano Concerto.’ No less a judge than Rachmaninov considered it the greatest piano concerto ever written, unsurprising when you consider its ravishing melodies – also a trademark of Rachmaninov’s beloved works in the genre.

For pianist Joyce Yang, who will be performing Grieg’s concerto with the Sydney Symphony this month, the appeal of the piece is immediate.

‘It’s a piano concerto that lives on its own planet,’ she says with a smile. ‘It doesn't sound like anything else. It has that signature sound – once you hear this melody, it seeps into your system and it's never going to leave you.’

Yang should know: this concerto has been a part of her life for more than 20 years, dating back to when she was a teenager studying at the prestigious Julliard School in New York City. ‘I learned it for the first time at, I think, the age of 15 or 16 years old,’ she recalls. ‘It was the assigned concerto for pre-college of Juilliard School concerto competition. And I was too young to enter, but I wanted to learn it like everyone else.’

‘It completely takes you to a new place,’ says Yang when asked what makes this such a special piece. ‘It’s an instant time travel and mood travel. That is its power, and why it survives through so many years. For me it has something to do with the melody – it’s not trying to be anything, and it’s the sign of a great composer that Edvard Grieg is able to write something that’s so unaffected, and it just soars.’

Perhaps it is no surprise that Grieg wrote such a perfect piano concerto. Like many great composers before him, he was an accomplished pianist: his mother taught him to play when he was only six, at 15 his talents were noticed and he was sent to the Leipzig Conservatory, and after graduating he made his living as a concert pianist for many years.

What is surprising is that, after having a huge critical and popular success with his Piano Concerto at the age of just 24, Grieg never wrote another one, preferring instead to keep tinkering with and revising his first, right up until the weeks before his death some 40 years later.

That, for Yang, is perhaps the most incredible thing about this concerto – just how beautifully written it is, and the way that the piano and orchestra are so perfectly balanced against each other.

‘This really is very well written for the piano and the orchestra,’ says Yang enthusiastically. ‘I never have to worry about balance, or being heard…I can really allow the piano to sort of shimmer.

‘The only thing that I always insist on is for it to not get too indulgent. Because once you put too much sugar in it, too much butter in it, I think it loses its innocent magic. It has to be like looking at a lake that no one has been to – it can’t have all the glitz and glam and have all these decorations that you sort of pay attention to, it has to be just that pristine lake, and you want to feel like you’re the only person there.’

Apart from this technical and compositional brilliance, Yang reiterates that she always finds this a profoundly moving and emotional piece whether she is sitting on stage or in the audience.

‘This piece, whether it's your first time hearing it or you've known it all your life, has the ability to really awaken something in you,’ she says, thoughtfully. ‘I hope it brings up a memory or it allows you to go to places in your mind that you've never been. This is a very unique atmosphere that Grieg is creating and I think the music speaks the loudest when it latches onto something that you already have, or it latches onto something that needs to come to life for the first time in your system, and something you've never felt before.

‘For me, I get moved and I get emotional during the concerts when it latches onto a memory of a person or an event that I didn't think about for twenty years. But because of some music, it just overwhelms and it brings me to somewhere I haven't been in a long time. So I hope this music has that power to either awaken something in you or take you to that place that you forgot about, living your busy lives, but it really has this incredible power to take you to places. So I hope you don't just look at the virtuosity of this music, but throughout it there's something that really finds meaning.’

In addition to the performances of the Grieg Concerto, Yang is also performing a solo recital in Sydney, at City Recital Hall, in a special one-off performance with a quite extraordinary program of music: Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons, three preludes by Rachmaninov, selections from Stravinsky’s ballet The Firebird arranged for solo piano, and – as if that weren’t enough notes for one evening – the entirety of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition.

It seems like an enormous challenge, a pianistic decathlon that only a masochist would willingly enter into. But although Yang acknowledges the vastness of the program, she points out that actually, broken down into their component parts, these pieces are really a series of individual miniatures.

‘The recital program depicts four composers that are wildly different, but they all wrote these pieces in small movements adding up to a larger scale,’ she says. ‘Putting them back to back like this…I think it highlights opposing compositions that exist in totally different worlds. The very poetic and beautiful ones glow in a different light, surrounded by something much more dramatic, and then the dramatic ones hopefully gain another power as well.

‘It is a bit schizophrenic,’ she acknowledges with a laugh. ‘But it kind of makes me feel like I'm talking to someone or collaborating with someone. I always like a solo recital program where I feel like I'm interacting with the composer…it makes me feel like I can play chamber music with all the voices [of the piano]. So it puts me at ease in a way.

‘It's a fast-paced program that brings out every colour and texture out of the instrument and gives you an overall view of what these composers were about. And really, they are all masterpieces that I love to play.’

‘I think the program is a lot of fun,’ she concludes with a laughs. ‘And I would be grateful for the audience to come on this journey with me.’