Shostakovich: The Autobiographical Symphonist

09 May, 2025

Dmitri Shostakovich is regarded as one of the great composers – but what makes his music so arresting? With the Sydney Symphony performing two Shostakovich symphonies in 2025, broadcaster, writer and self-avowed Shostakovich devotee Paolo Hooke explains why his work remains so compelling and so relevant today.

Listening to a symphony by Dmitri Shostakovich (1906–1975) is like reading a gripping autobiography. The composer lived most of his adult life under the long shadow of Joseph Stalin and his despotic regime and poured his anxieties and fears into his music, so we have something close to a real-time diary of Soviet Russia in his symphonies.

In 2025 Sydney audiences will hear two pivotal chapters in this thrilling story, when the Sydney Symphony Orchestra performs Shostakovich’s Fifth and Fifteenth symphonies in September and July/August. The Fifth is an autobiographical symphony of an artist living through, and surviving, an age of terror, while the Fifteenth is his symphonic swansong and summary of his extraordinary life.

The experience of hearing a Shostakovich symphony live is unlike anything else in classical music. It is an exhilarating journey through terror and tragedy, a story of suffering as told by a composer who witnessed terrible events and feared for his life. Shostakovich is a master of ambiguity - his symphonies often convey contradictory emotions, offering multiple interpretations. And we should embrace the equivocation! After all, it is what allowed Shostakovich to maintain his moral and artistic integrity under the Soviet regime, and arguably saved his life. Not only is Shostakovich ambiguous, he is brooding, his music glowering with anger. But wouldn’t you be bitter if you had the misfortune of living in a totalitarian state? Wouldn’t you be sour if a cruel regime condemned your work? Wouldn’t you be resentful if you were publicly humiliated and people crossed on the other side of the street to avoid you?

Shostakovich experienced all this and more, and his Fifth Symphony is the riveting account of his own suffering. It was composed in 1937 amidst Stalin’s Great Terror and after the denunciation of his celebrated opera, and it marks the turning point in Shostakovich’s career when he was forced to express himself in a more ‘accessible’ way. Gone is the brazen brilliance of Shostakovich’s youth, which we hear in the grandiose and bombastic Fourth Symphony, replaced by a steely resolve as the composer confronts for probably the first time the central theme of his life: anti-Stalinism.

Sydney Symphony Principal Guest Conductor Sir Donald Runnicles, who will conduct the Fifth Symphony in September, says that while he is very aware of the circumstances under which Shostakovich wrote this autobiographical symphony it doesn’t really affect the way he approaches it because it is such an accomplished symphony. Shostakovich, says Sir Donald, was one of the greatest symphonists, ‘who took this Beethoven ‘classical’ model of four movement symphonies, and elevated it to a level where in Shostakovich's time, he bore witness to what was happening in his life, what was happening in Russia. His symphonies become these snapshots in time.’ Or as the Russian conductor Yevgeny Mravinsky said, ’It shatters one with its force and depth of philosophic thought, enriched in severe, real classical form in all its simplicity and greatness.’

’You really don't have to understand any of the circumstances surrounding the creation of this work,’ says Sir Donald of the Fifth. ‘It embraces supremely musical disciplines. It’s profoundly sad that that same sense of struggle, that same sense of autocratic governments, that same sense of people living in fear – in 2025, nothing has changed.’ Sir Donald says it is very well documented where this symphony came in Shostakovich’s life, where he literally feared for his life. ‘He expected to be picked up, like a lot of other artists, during the night. He kept a suitcase at the door ready to be picked up by the secret police. This was the Stalinist world in which he lived.’

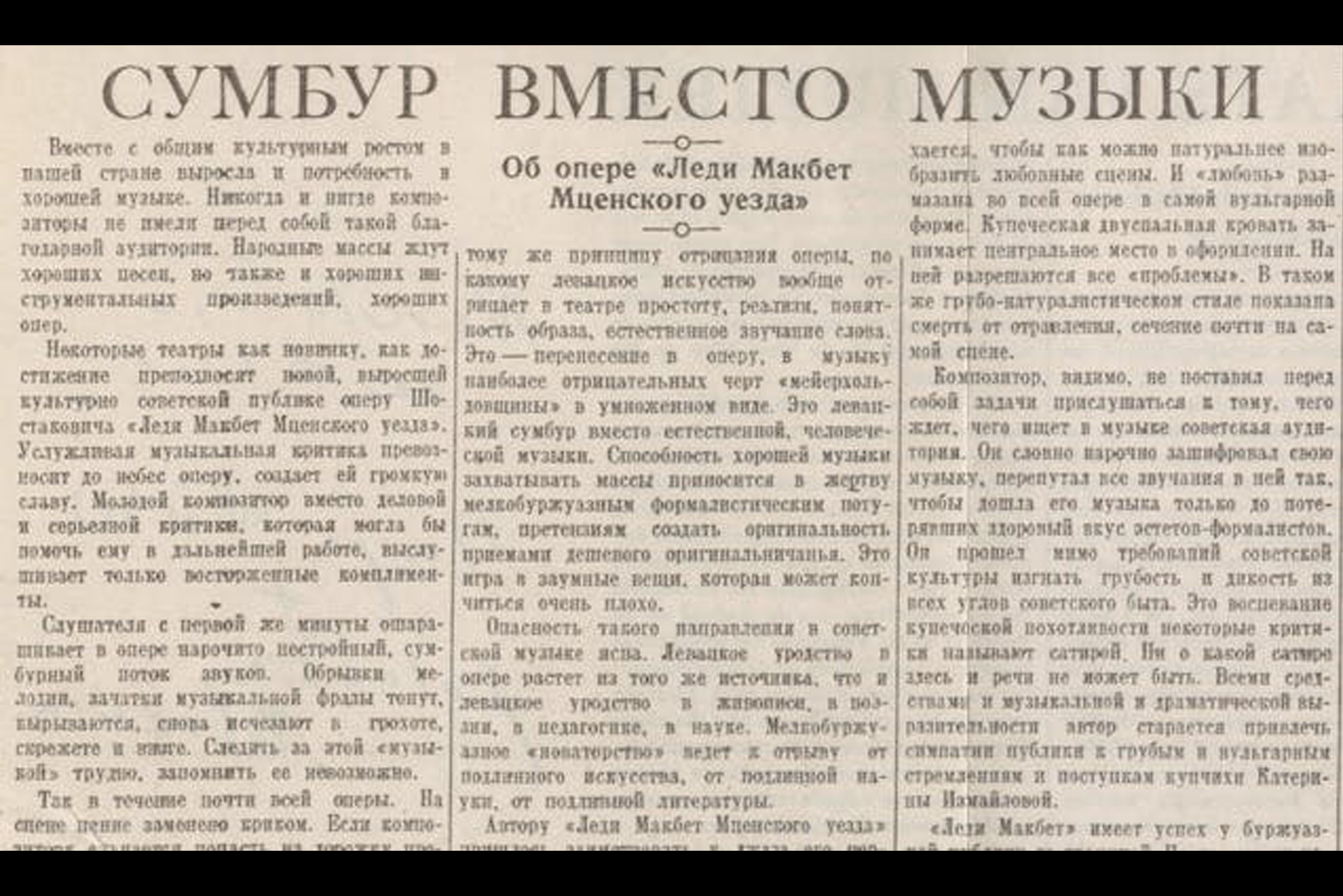

Shostakovich feared for his life because his existence had changed forever in 1936. The high-flying composer, still in his twenties, had enjoyed international fame with the success of his racy opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, which premiered in January 1934. However Stalin’s visit to a Moscow performance of Lady Macbeth on 26 January 1936 was to prove fateful. Ominously, Stalin left before the opera’s final scene. Two days later, an editorial in the Party newspaper Pravda, ‘Muddle Instead of Music’, censured Lady Macbeth. This was followed by another Pravda editorial, ‘Balletic Falsehood’, which condemned the composer’s ballet The Limpid Stream. As an ‘enemy of the people’ Shostakovich was ostracised from society and driven to the edge, awaiting destruction. As his son Maxim describes; ‘Under Stalin, every day as Shostakovich left home, he would take a small packet of soap and a tooth brush with him, not knowing if he would return.’ As the composer recounts in his controversial but reliable memoirs Testimony; ‘Two editorial attacks in Pravda in ten days – that was too much for one man. Now everyone knew for sure that I would be destroyed. And the anticipation of that noteworthy event – for me at least – has never left me.’

Shostakovich’s response to the threat of destruction was to compose what may appear to be a rehabilitation symphony, that repaired his reputation and restored his image as a ‘faithful son’ of the Communist Party. In a regime that regarded a man as a mere cog in the machine, another body to be placed on the pile if the state so desired, Shostakovich’s music was necessarily ambiguous. The Fifth Symphony appears compliant to the regime’s demand that music be ‘optimistic’: witness the repeated high-register A in the strings and blaring D major in the final movement, which seems triumphant. Yet all is not what it may appear. The smile is forced, the rejoicing ironic in the style of the Russian saying, ‘Kiss, but spit’, a hollow victory that is a parody of forced rejoicing. As Shostakovich explains in Testimony; ‘It’s as if someone were beating you with a stick and saying, “Your business is rejoicing, your business is rejoicing”, and you rise, shakily, and go marching off muttering, “Our business is rejoicing, our business is rejoicing”.’

In a terror-stricken age, Shostakovich wrote the memoir of the Russian tragedy of the 20th century, voicing the suppressed thoughts and feelings of his fellow citizens. At the electrifying premiere of his Fifth Symphony in Leningrad in 1937, the audience gave a frenzied ovation that lasted more than 30 minutes. As the composer’s close friend, the conductor Kurt Sanderling recounted of the Moscow premiere in 1938; ‘The audience was very receptive to Shostakovich's message, and after the first movement we looked around rather nervously, wondering whether we might be arrested after the concert...The vast majority of the audience knew perfectly well what it was all about... It perfectly reflected the sentiments that were uppermost in our minds.’

Audiences at the premiere would have been spellbound from the opening note, as the Fifth begins with a powerful and unnerving doom-laden motto-theme that demands our attention. The lyrical and tender passages that follow are notable for their purity, before the entrance of a menacing presence that culminates in a monstrous Mahlerian march. The second movement of caustic humour has been described as the aggression of a soulless negative force. The slow third movement Largo is one of Shostakovich’s finest lyrical creations. It contains two climaxes in which the intensity of emotional outpouring for the countless victims of Stalin’s Terror is white-hot, reflecting the enormous inner repression required in an oppressive state. It brought many audience members to tears at the work’s premiere. Saturated with melancholy, the Largo is scored for strings and woodwind, giving it an intimate chamber-like quality incorporating the tradition of Russian funerals. Shostakovich splits the number of strings into three parts to increase the number of voices, a stream of consciousness depicting the nerve-racked hypersensitivity of the age in which survival was largely a matter of chance.

‘Show me the man and I'll show you the crime’ was the notorious brag of Lavrentiy Beria, the longest-serving head of the secret police during Stalin’s rule. The sweat of fear in which anyone could feel they were the next victim was a permanent condition of the Soviet citizen throughout Stalin’s Terror. Shostakovich experienced this fear following his condemnation in 1936, sleeping in the stairwell outside his apartment, awaiting the tip-toeing of death on the stairs. Maxim Shostakovich describes the third movement as ‘the last night at home of a man sentenced to the gulag.’

Shostakovich composed his Fifth Symphony in an era when millions were banished to the Gulag, the Soviet network of forced labour camps located in the remote regions of Siberia and the Far North. ‘The majority of my symphonies are tombstones,’ says Shostakovich in Testimony. ‘Too many of our people died and were buried in places unknown to anyone, not even their relatives. I’m willing to write a composition for each of the victims, but that’s impossible, and that’s why I dedicate my music to them all.’

Whereas the Fifth is Shostakovich’s memorial and autobiography of life under terror, the Fifteenth Symphony, composed in 1971, is a disconcerting farewell and summing up of his life, laden with self-quotation and allusions. By this time Shostakovich’s health was in decline, and the symphony is an appraisal by a slowly dying man of a lifetime of composition. Shostakovich asks uncomfortable questions about life and music in his final symphony, offering no answers, only ambiguity.

‘To emphasise the work’s autobiographical nature, Shostakovich either directly quotes from, or at least conveys the atmospheres of, all his previous symphonies,’ writes the British conductor and Shostakovich specialist Mark Wigglesworth of the Fifteenth. ‘Along with references to his operas and film scores, not to mention excerpts from, among others, Beethoven, Rossini, Glinka, and Wagner, all are knitted together into some kind of musical biopic. That the work does not come across purely as a homage to Shostakovich the man, and the fact that it never resembles an incongruous patchwork collage is an enormous tribute to Shostakovich the composer. As always, the man and composer are inseparable, bound by a prescriptive yet creative thread perhaps unique in the history of music,’ writes Wigglesworth. As Shostakovich told his close friend Isaak Glikman, “I don’t myself quite know why the quotations are there, but I could not, could not, not include them.”’

His Fifteenth Symphony is frequently bewildering, with the first movement evoking an apparently innocuous toy shop. As Kurt Sanderling describes; ‘In this ‘shop’ there are only soulless dead puppets hanging on their strings which do not come to life until the strings are pulled. This first movement is something quite dreadful for me: soullessness composed into music, the emotional emptiness in which people lived under the dictatorship of the time.’ The sombre second movement alternates between the private and the public, with a third movement of grotesque humour. The extraordinary world-weary final movement quotes Wagnerian motifs of tragedy and death, ending in percussive sounds that suggest hospital machines; Shostakovich composed much of the symphony while in hospital. The final chilling notes of Shostakovich's symphonic output are some of the most nerve-jangling sounds one can hear in a concert hall.

Fifty years after Shostakovich’s death on 9 August 1975, we marvel at a composer who created music of immense emotional power in the most extreme circumstances. Dmitri Shostakovich, the autobiographical symphonist and master of ambiguity, managed to chronicle the horrendous human suffering he witnessed. His timeless music remains eternally relevant.

Hear Shostakovich’s Symphony No.15 conducted by Kevin John Edusei when Javier Perianes performs Saint-Saëns (30 July – 2 August), and then Donald Runnicles conducts Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony (12–14 September).