Donald Runnicles on the Search For Meaning In Music

28 March, 2023

The Sydney Symphony’s Principal Guest Conductor returns to Australia in April, presenting two concert programs with threads tying them close together – from the close relationship between Brahms and the Schumanns to Elgar and Shostakovich’s responses to war and loss.

By Hugh Robertson

Sir Donald Runnicles is a man who believes deeply in the power of music to bring people together.

Some of his earliest memories are of his father’s choir in Edinburgh, watching and listening as dozens of voices combined into one powerful wall of sound.

That philosophy has been the central ethos of his long and celebrated career, at the core of his many engagements and positions around the world today – whether as General Music Director of the Deutsche Oper Berlin, Music Director of the Grand Teton Music Festival in Wyoming, Conductor Emeritus of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, or as Principal Guest Conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra.

Music, for Runnicles, is akin to a religious experience, one that is unique and impossible to replicate.

“It is an incredible blessing when a lot of people are together and experiencing a concert,” says Runnicles. “And the moment that last chord has died away, it is gone. This is a communion, in a very, very holistic way, where people are sitting together and enjoying the great masterworks. And that is what has always inspired me, the process of making music with and for people.”

The ‘with’ part of that equation is something the Sydney Symphony knows all too well. Runnicles’ relationship with the Orchestra stretches back to his first visits to Australia nearly 25 years ago, and it is one he treasures deeply as he and the Orchestra have grown and developed together.

“Longstanding relationships are based on mutual respect, mutual trust, and a degree of mutual humility,” he said to Limelight back in 2019 when first announced as the Orchestra’s Principal Guest Conductor. “Over a period of time, one’s music making is informed by all of those [things], and as you grow as an artist so the relationship grows. I would say the most important aspect of all of that is a degree of vulnerability – that people, musicians, artists are willing to be taken somewhere that they might not have thought to go to before.”

The ‘for’ part of Runnicles’ philosophy will be clear to anyone who has ever attended one of his concerts and experienced the way in which he draws musical threads together. Runnicles is passionate about designing concerts that connect with each other, that present a coherent theme or through-line for the audience.

“It is my conviction that audiences enjoy a journey,” says Runnicles. “In putting together orchestral programs, one is obviously looking for pieces that go well together, that shine off one another.”

In April, Runnicles returns to the Sydney Symphony for two concerts that perfectly demonstrate this desire for connection not just between the composers on the program, but between the audience and the performers.

The first concert is a journey to the heart of the Romantic era, and to the close friendship between Robert Schumann, Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms.

Robert Schumann was one of the great Romantic composers, considered the heir to the German symphonic tradition handed down from Beethoven to Schubert and Mendelssohn. Clara Wieck was one of the most celebrated pianists of the era and a talented composer in her own right, a one-time child prodigy who would go on to redefine the role of the soloist over the course of a long and distinguished career.

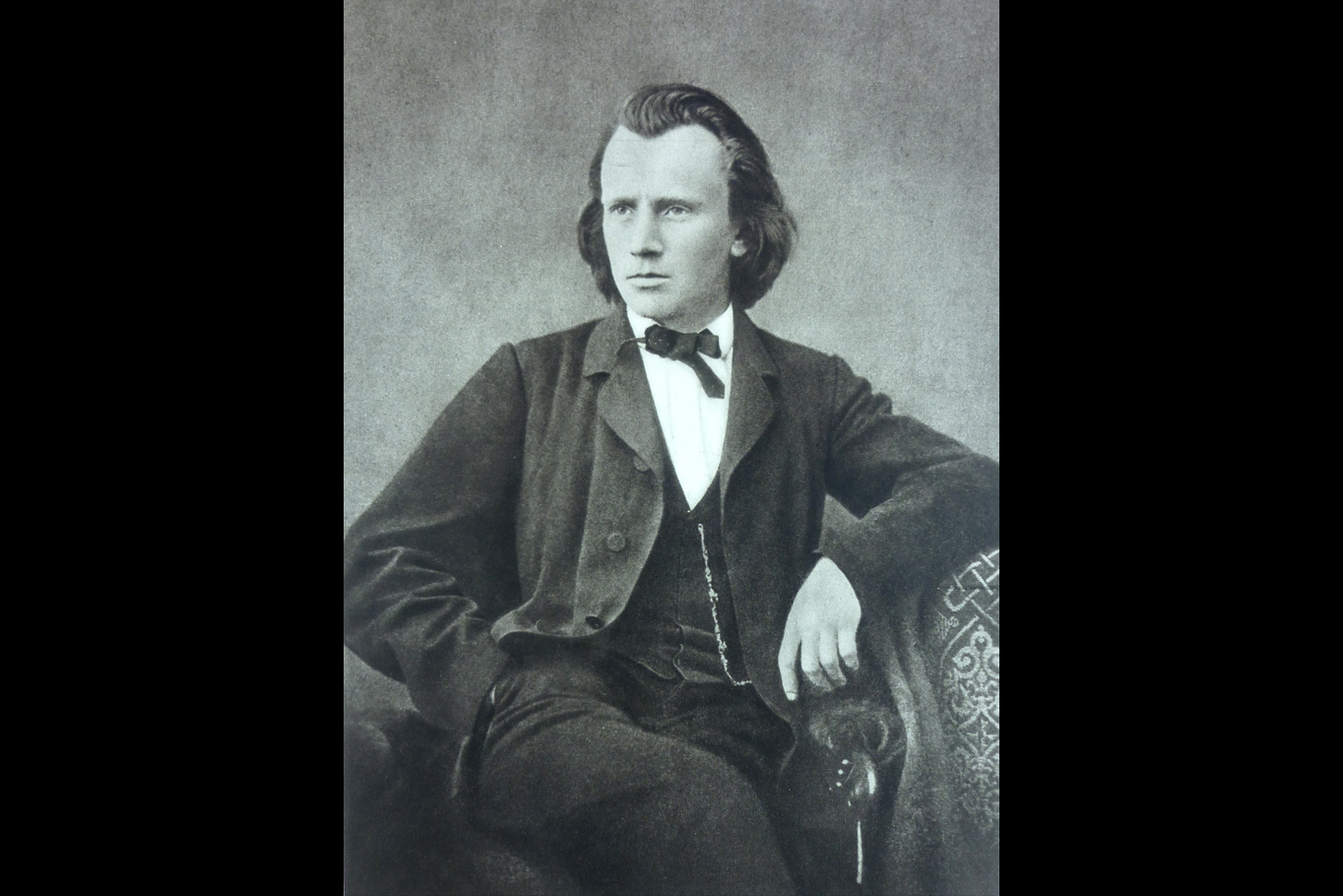

Brahms was a generation younger than the Schumanns, but they saw in him the same spirit, recognising his talents and boosting his career – after their first meeting when Brahms was just 20, Robert wrote that Brahms was "fated to give expression to the times in the highest and most ideal manner".

Robert and Clara were utterly devoted to each other, and so much of their relationship is captured in this concerto – one of the concerto’s main musical themes is based on the notes C-B-A (C-H-A in the German note-naming system), thought to represent the name ‘Chiara,’ Robert’s nickname for Clara – and after Robert’s death at the age of just 46, Clara performed this concerto across Europe for the remainder of her life and career, doing more than anyone else to cement her late husband’s legacy. Around the time of Robert’s death Brahms began to fall in love with Clara – and although (as far as we know) their relationship remained platonic, they remained close until Clara’s death in 1896, just one year before Brahms.

“Robert Schumann was, in his own way, a revolutionary as a composer, as a musician,” says Runnicles. “And he sensed very much that the young Johannes Brahms was a worthy successor to him, and there's this three-way devotion and love.”

Runnicles is one of the world’s leading interpreters of Brahms. He led the Sydney Symphony in performances of Brahms’ Violin Concerto with Augustin Hadelich last year to rave reviews, and the symphonies often feature on his programs around the world. When asked what it is about Brahms that speaks to him so, Runnicles pauses for a moment – as if trying to find the words to describe the totality of the connection.

“There’s a deep humanity in the music,” he says eventually. “It's never showy for showy’s sake. It's deeply thought-through. It is extremely emotional without the heart being on the sleeve – there’s great restraint shown in it. And there is a beauty there.”

“There was a great deal of sadness in Brahms’ life, partly because of his long, long, platonic love for other people – the most famous of all being Clara Schumann – and there was never, ever going to be a chance for there to be an actual romantic relationship there. And when you look at this pictures of the young Johannes Brahms, there was this dashing, incredibly handsome young man who was devoted to his music, devoted to his piano playing, and yet through his long, long and incredibly industrious life, he remained a bachelor to his final days.”

“So I feel there's always this yearning in his music, even when it is at its most sunny. There is this yearning for humanity, yearning for warmth, of course, yearning for meaning.”

“In the Schumann Piano Concerto, too, there is a plaintive aspect to it,” he continues. “There is a struggle in this music. And as we know that Robert Schumann all his life struggled with mental health. I'm not suggesting that you only need to know about that, but there is such beauty there, and yet something very fragile about that beauty.”

This concert opens with a work by contemporary German composer Detlev Glanert, titled Idyllium. Here, too, are the connections deep and multi-layered, as Runnicles explains.

“Detlev Glanert and I have been friends for decades,” he says, “and he worships at the altar of Johannes Brahms. He would readily tell you that Brahms is the most profound influence on his music. Detlev wrote this piece as a musical tribute specifically to the Second Symphony.”

“As the piece evolves – and it's only seven or eight minutes long – you realise that even though it is considerably more modern in its tonal language, it's still very much the Brahmsian world.”

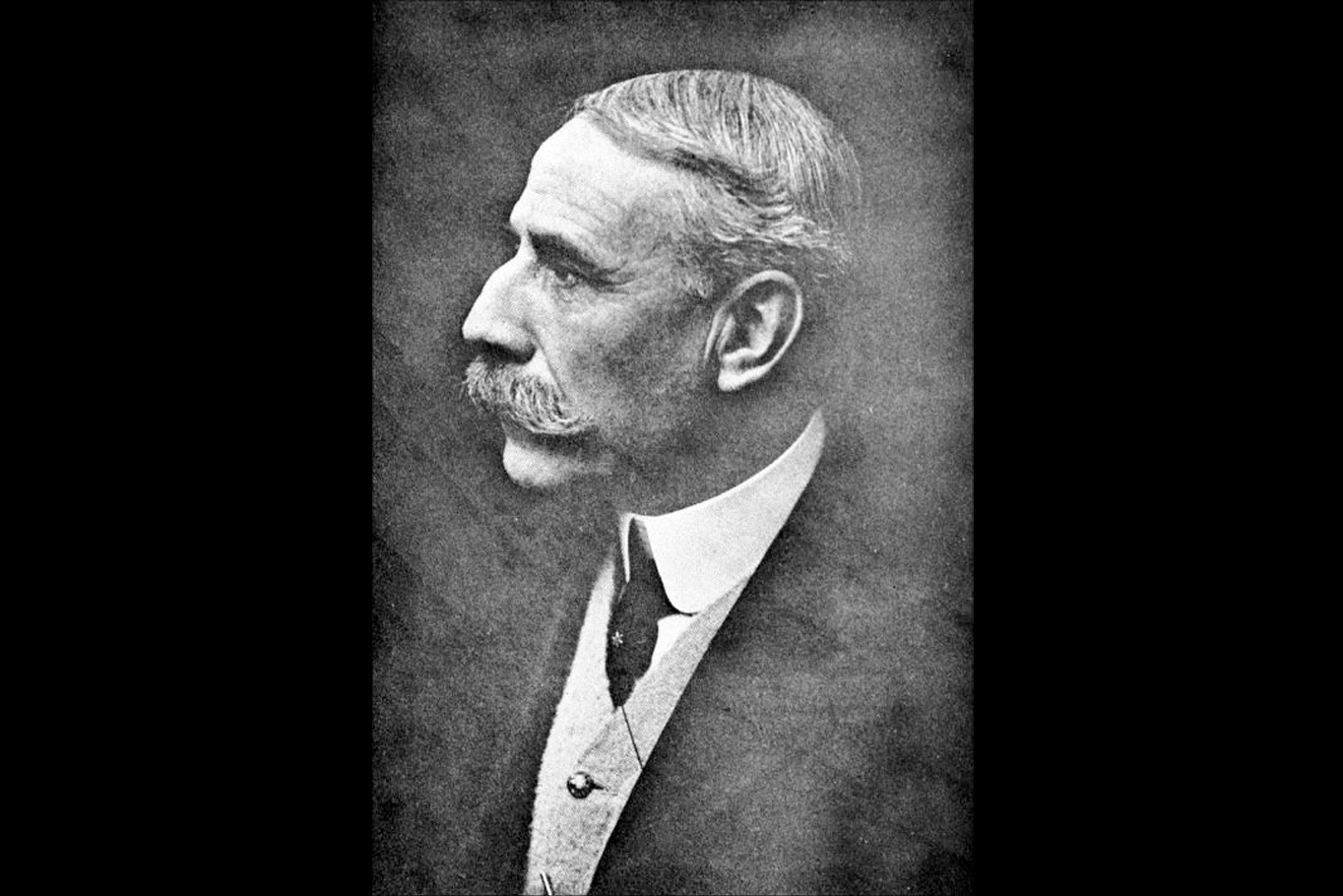

The second concert program that Runnicles has devised has more of a thematic than a personal connection. Edward Elgar’s Cello Concerto, written in 1919 and responding to the horrors of World War I, is paired with Dmitri Shostakovich’s Tenth Symphony, first performed in 1953 and a powerful reflection on the death of Joseph Stalin and the devastation and suffering caused by his regime.

Though few would put the two composers in the same category musically – even historically – these two pieces share a similar perspective. Both were written following eras of tremendous upheaval in their countries, and, written when the composers were older and reflecting on their lives, lamenting all that was lost and the destruction of the world they knew.

“Both works are deeply personal responses to loss,” explains Runnicles. “The whole work is a feeling of the loss of human dignity, the loss of the spirit of the individual in that incredibly authoritarian world in which this young prodigious composer grew up. And even as the work ends in an optimistic, more ebullient way, so often with Shostakovich, there's something a tiny bit hollow about it.”

“Similarly with Edward Elgar. There is a sense in this work of a loss of innocence, a loss of a world that Edward Elgar grieved, the pre-First World War era. And in that way, I felt that these pieces make sense together.”

One of the things that has long fascinated biographers about Elgar’s concerto is that it was the final large-scale piece that he ever wrote, despite living for another fifteen years after its completion. Here too is a connection with Shostakovich, as Runnicles points out – although he would go on to write much more music after his Tenth Symphony, his musical language became more and more minimalist, as though a slow depletion of his energy and life-force.

Runnicles believes that it wasn’t just the circumstances of their era that weighed both men down, but their own mental health issues that affected them throughout their lives. Although it is near-impossible to diagnose historical figures in modern terminology, there is no doubt that both composers suffered terribly from mental illness – unsurprising, given the trauma and upheaval they both lived through.

“Here was a composer, Dmitri Shostakovich, who also was plagued by the demons of his country, and a man who could plunge into the deepest depression,” explains Runnicles. “And of course, we know from Edward Elgar that he was – as we would call it today – a manic depressive, some would say bipolar. And he would always carry that inferiority complex, which is something so quintessentially British. I think there was that sense of him wondering after writing the Cello Concerto, ‘Is there anything I could write now that would be worthy of being heard?’”

“And that has us all full of conjecture. Was there not more to be written? But isn't it wonderful that we are still very open to interpreting these works, and taking these works that were written 100 years ago, 50, 100, 150 years ago, and taking those snapshots in the composers’ lives, and then projecting them in some ways on our own mental health or our own state of being. It's endlessly, endlessly meaningful.”

Perhaps it is that search for meaning that unites the four works in these two concerts. That search is indeed an endless one, and is unique to every performer and listener who encounters these works: we have no plot or text to follow, and very little information from the composers themselves on what these pieces are ‘about’, and so we can only bring ourselves to the music – our experiences, our memories, our loves, our losses. That is what makes orchestral music so endlessly fascinating, and so rich – we never know what we will find in a performance until we experience it ourselves.

For Runnicles, even after all these years of performing, that is what inspires him to keep going – the knowledge that every single performance is unique, and a new opportunity to affect people’s lives.

“It is always one of those mysteries, when you have performed a work for 1500 people,” he says, thoughtfully. “How do they all leave the hall? What fills their minds? What fills their souls? Did they like it, did they not like it? I would like to think that many people leave a concert changed, in some way. Given food for thought.”

“I have a longstanding relationship with the Atlanta Symphony Choir and Orchestra, and their iconic leader, Robert Shaw would say to them, ‘In this performance, you have to assume that many people are hearing this work for the first time. But you also have to assume that many people are hearing it for the last time.’”

“And I think, with that as a backdrop, one is hoping that one is touching people.”