Lifting the Protecting Veil

12 February, 2024

Cellist Matthew Barley and Principal Guest Conductor Sir Donald Runnicles explore the mysteries of John Tavener’s The Protecting Veil, an extraordinary work for cello and orchestra that receives its Sydney Symphony premiere in March.

By Hugh Robertson

English composer John Tavener (1944–2013) is one of the most fascinating figures in twentieth century music, his life one long journey seeking beauty, truth and meaning through music.

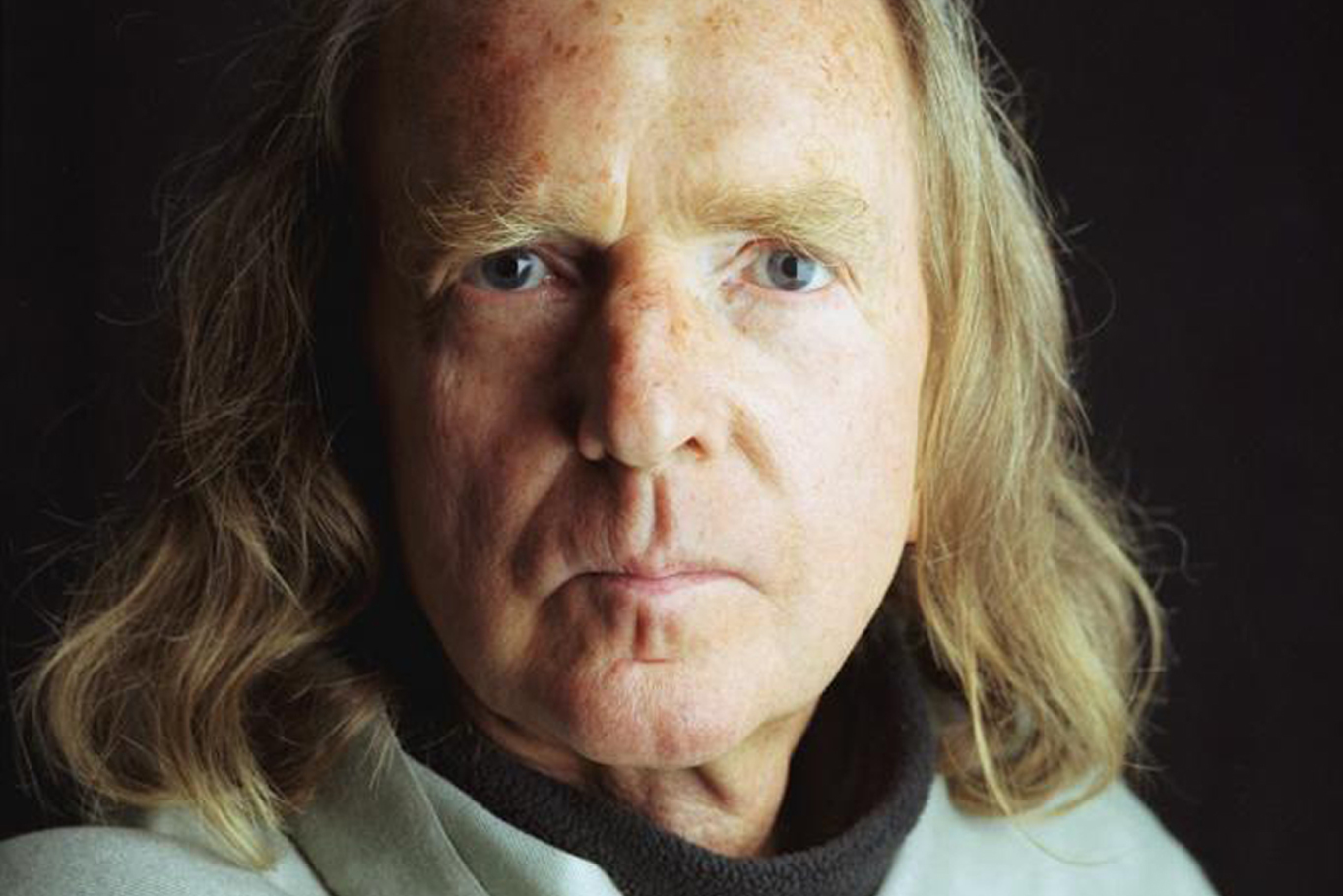

He was hugely successful throughout his career, from a piece recorded and released by The Beatles’ record label in 1970, to his Song for Athene which was sung at the funeral of Princess Diana. Yet Tavener was far from a celebrity composer: he converted to Orthodox Christianity in 1977, and his music great increasingly spiritual and contemplative in the following decades. He even looks like a man out of time: the face that stares out from his album covers should perhaps be tucked away in a monastery in the 14th century, pouring over manuscripts and chanting psalms at evensong.

Despite the intense meditation and inwardness – or perhaps because of it – his music has remained incredibly popular. When he died English composer John Rutter remarked to the BBC that Tavener had the ‘very rare gift’ of being able to ‘bring an audience to a deep silence.’

One work that has always inspired silence and contemplation is The Protecting Veil. Premiered by cellist Steven Isserlis at the 1989 Proms it was an instant hit, the resulting album becoming a best-seller. This extraordinary work will receive its Sydney Symphony premiere in March, with English cellist Matthew Barley as soloist conducted by Chief Conductor Sir Donald Runnicles in a program that also features music by Wagner and Mendelssohn.

‘The Protecting Veil is breathtaking,’ says Runnicles. ‘It’s this long meditation for cello and string orchestra. It's deeply felt, meditative music that makes time stand still – and for us in the audience, it is a chance to be still.’

‘The whole thing is written so beautifully, so tightly,’ says Barley. ‘It takes the listener on a really huge emotional journey. It's an absolutely unique experience.’

Matthew Barley knows The Protecting Veil as well as anyone alive. He has performed it multiple times over the past 30 years, and his recent recording of it was praised as ‘utterly beautiful’ (Gramophone) and ‘a performance of great tenderness and eloquence’ (BBC Music Magazine). And it is clearly a work that he is deeply passionate about. These Sydney concerts will be some of Barley’s only performances anywhere in 2024 – he has otherwise cleared his schedule in order to devote his time to a huge composing and recording project that has been in the works for 15 years. But he couldn’t ignore the offer to perform this extraordinary work again.

‘That was irresistible,’ says Barley with a smile.

‘It's an extraordinary experience to play. It’s really amazing. It's like...’ He pauses, searching for a comparison. ‘I don't know what it's like. It's not like anything else.’

‘It’s one of the biggest cello concertos ever written,’ he continues, ‘and an absolute marathon for the cellist. It involves a huge amount of physical, mental, emotional stamina to play it. The cello plays the first note and the last note and doesn't stop playing in between. And yet the musical material is quite simple in many ways.’

Barley has a deep and intense connection to the work itself, developed over many performances. But he also has a connection to Tavener, whom he met several times and who gave him feedback on his performance directly.

‘We met professionally several times,’ says Barley. ‘I ended up spending a day with him, not that long before he died, playing The Protecting Veil. We had a fascinating day together, which was really, really illuminating.’

‘John was brilliant’, continues Barley with a smile. ‘He had this very, very thin face and long hair. He was a very spiritual, inward, religious man, but he also had a wicked sense of humour and loved to collect vintage sports cars. I wish I'd got to know him better. I’m sure he must have been a fascinating person to really get to know.

‘Working with him on the cello was also great. He listens in a way that’s very like his music – he’s listening to something way, way through the notes. And his feedback was very choice: he was much more interested in talking about the atmosphere and the spirit behind it, and the sort of general sound worlds [than the minutiae of how to play].’

There is no doubt that the spirit of The Protecting Veil is immense. Though as Donald Runnicles is quick to point out the vastness of the atmosphere is conjured by surprisingly few notes. ‘It's not a great deal of material,’ he says. ‘But it is hypnotic, it lures you into this trance. It’s hard to describe until you hear the work, and then I think those listening to it for the first time will ask, “Where has this music been all my life?”’

Barley had that exact experience the first time he heard the work – but his reaction was even more intense given he was sitting in the cello section of an orchestra performing the piece.

‘I’d never heard the piece before, and I remember – I mean, I can still locate this visceral memory of thinking, “What is this music? I really want to play this.” I was open mouthed with excitement and wonder.

‘I don't think I've ever had such a reaction like that. It is like nothing else.’

Barley tries to replicate something of his first hearing of the piece whenever he performs it, aiming to create an atmosphere of community and a shared experience that everyone is taking part in, rather than a performer presenting something to an audience.

‘It’s a very sacred experience to be able to share music with a lot of other people. And in that communion, if it works, I get to a place where I don't feel I’m the performer and this is a piece of music, and those people over there are listening. Instead there's something happening energetically that we're all taking part in.

‘I think one of the beautiful things about instrumental music is that the variety of personal experiences everybody can have is endless. Some people daydream and think about their life. Some people are seeing images. Some people are fiercely connected with watching the musicians. And every one of those ways is perfect.

‘I find it astonishing that every single person is having a different experience, but are united in that moment of sharing that sound. It’s a very special thing.’

Runnicles couldn’t agree more, and thinks that this concert – which also features works by Wagner and Mendelssohn, two of his favourite composers – will be something very special indeed.

‘The live concert experience is so essential to experiencing music as it should be experienced,’ he says. ‘Being in a hall and experiencing that collective response.

‘There is literally something in the air. If there's a performance that is electric or moving or absorbing, you really can feel that and you can only feel that in the context of a large space. Each and every member of that audience will relate to that music in his or her way…and I think it's one of the most beautiful things about live music.

‘In this program of Mendelssohn and Tavener and Wagner, there is a vibe, there is a frequency. There is a feeling that “I'm part of something very special for these two hours.”

‘And when that final chord has evaporated, it’s gone, it's over. You can't replicate it. You might have recorded it, but you can't replicate that visceral feeling of being in an audience at a concert in this glorious Sydney Opera House.’